Manifestations (préventes, bourses, etc...)

Exposition internationale et bureau temporaire Braphil '15

WATKINS Paul Royal Philatelic Society London

Mail between Great Britain and France, 1791-1815

Although France did not declare war on Britain formally until February 1793, the effects of the 1789 Revolution were being felt, not least in the numbers of émigrés fleeing to these shores. The steady stream which had originated with the 1685 repeal of the Edict of Nantes and the consequent revival of religious intolerance which had helped enrich British industry with the influx of skilled protestant Huguenot craftsmen, grew to a flood in the 1790s.

The involvement of the Royal Navy in the French Wars – patrolling the coast of France in the Channel, the Atlantic, the Mediterranean and the Caribbean with the blockade of significant ports – coupled with a period of neglect in the French Navy – resulted in British control of sea-based trade and shipping. In turn, France became the supreme military power in mainland Europe during these years, largely through the military talent of a couple of handfuls of men – including Napoléon Bonaparte – who might not ordinarily have had the opportunity to develop their gifts had it not been for the Revolution largely « clearing the decks » of the Ancien Régime officer-class.

In the short (14 months) truce that followed the Peace of Amiens in March 1802, relatively normal trade and postal traffic resumed but the main postal link – the Dover-Calais packet – was stopped at the end of May 1803 and problems of communication escalated. It is from this period that there was an agreement between the French government and the Thurn & Taxis Post for the routing of mail to and from Britain via Hamburg. Mail travelling this route was identified with a Thurn & Taxis « rayon » hand-stamp and additional postal charges. The system lasted until Napoléon’s « Decree of Berlin » on 21 November 1806 – in response to the British Order in Council (16 May 1806) which had declared a general blockade on Channel ports between Brest (Brittany) and the mouth of the Elbe – itself declaring a suspension of all trade and communication between France (including French-controlled areas of Europe) and Britain. This was Napoléon’s « Continental System » for reducing Britain by attacking her commercially, as he was unable to invade the country or defeat the Royal Navy.

Between the end of 1806 and early 1814, when Allied forces defeated France and Napoléon was exiled to Elba, there was no official mail service between the two countries. As had been the case earlier in the War, alternative methods were used to convey letters – but in an increasingly intense and inventive manner.

Forwarding agents increased their business – those based in the French Channel ports, in particular; they had the contacts that enabled them to place packets of letters with captains of « neutral » ships, particularly American, Dutch & Scandinavian vessels, for carriage to a British port.

Informal « smuggling » went on – with independent ship – and boat-owners prepared to run the risk of capture by the Navy – or clandestine travellers carrying mail as a favour and mailing it in the local post on their arrival.

The onerous Hamburg route was « short-circuited » by mail travelling with ships from the East of England to Holland and posted in the Dutch mails.

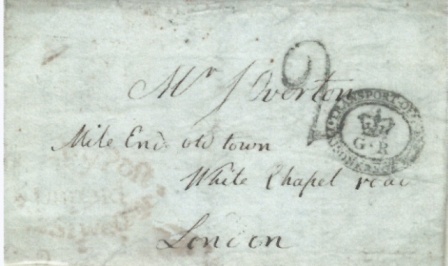

1811 letter from British Civilian détenu in Paris lodgings delivered in London through the Transport Office

1811 letter from British Civilian détenu in Paris lodgings delivered in London through the Transport Office

The agreement by which letters from POWs and civilian detainees on both sides were allowed to travel – albeit under firm surveillance – was suspended for a while, following the Berlin Decree, then gradually revived. Not all such mail was as controlled as both governments liked to believe – there is a letter in this display which travelled « direct » via Germany, escaping the attentions of both the Cabinet Noir and the Transport Office.

The false reassurance of the First Restoration period – when the ungrateful Louis XVIII was placed on the throne by the victorious Allied Power – lasted for about a year, before Napoleon’s return from Elba, the « 100 Days » and the decisive battle at Waterloo in June 1815. The mail system had been restored by the Treaty of Paris, the cross-Channel packets recommenced and unofficial transport of mails was made illegal – only for the chaos caused by the exiled Emperor’s return to create a reversion to previous methods of forwarding the posts.

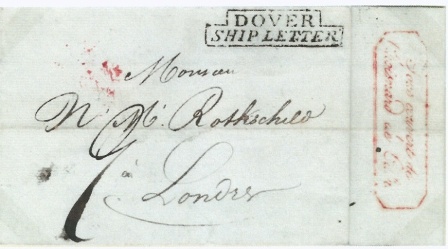

April 1815 – Paris letter delivered during the « Hundred Days » by private ship organised by Calais forwarding agent and landed at Dover.

Following Waterloo, the status quo was re-established on a permanent footing mid-July 1815.

The 25 years’ war between France and Britain created a lot of problems – and opportunities – for postal traffic and for the postal historian.