Manifestations (préventes, bourses, etc...)

Exposition internationale et bureau temporaire Braphil '15

NICK MARTIN Royal Philatelic Society London

The influence of the French occupation of « BELGIUM » 1793-1815

Belgium has over the centuries suffered countless military invasions and incursions by Burgundians, Dutch, French, English and Germans. However, during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic periods we can for the first time consistently find evidence in letters of how an occupier can affect the military, administrative, political and social structure of the country and of course postal history is one of the finest ways in which we can actually see documentary evidence of a country’s history. First evidence of French occupation was probably the erection of “trees of liberty” usually a pole or a trimmed tree with some symbol such as a revolutionary bonnet or a garland perched on top. Seen on letter heading. Here we have a rather tatty reproduction of a contemporary painting showing the town hall and belfry in Bruges. The revolutionary bonnet was the attire of many revolutionaries. This seems to have been re-adopted today but not for the same reasons !

Belgium has over the centuries suffered countless military invasions and incursions by Burgundians, Dutch, French, English and Germans. However, during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic periods we can for the first time consistently find evidence in letters of how an occupier can affect the military, administrative, political and social structure of the country and of course postal history is one of the finest ways in which we can actually see documentary evidence of a country’s history. First evidence of French occupation was probably the erection of “trees of liberty” usually a pole or a trimmed tree with some symbol such as a revolutionary bonnet or a garland perched on top. Seen on letter heading. Here we have a rather tatty reproduction of a contemporary painting showing the town hall and belfry in Bruges. The revolutionary bonnet was the attire of many revolutionaries. This seems to have been re-adopted today but not for the same reasons !

The earliest evidence in letters is from the period of the first (temporary) invasion, when the French revolutionary armies under General Jourdan attempted to overrun the country. Letters of this period often contain military references or evidence of the impact of the revolution itself. We find evidence of the military commanders in the invading armies. They were similar to the Zampolit in the later Soviet armies who worked alongside army commanders and who in theory held lower rank but in practice far outranked them.

Here we have a letter from the EXPEDITION DE LA BELGIQUE. Under the regime post offices were set up in each army and managed by civilian employees who were appointed by the representatives. Of interest here is the endorsement “Expédié négativement” (sent free of postage) and the OO charge on the front.

Revolutionary Town Names

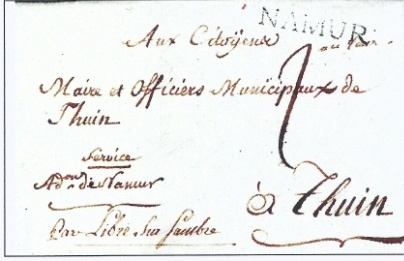

Many towns in France adopted new “Revolutionary” names either by choice or imposition when their names contained references to royalty, the nobility or the Church. Some 80 towns were re-named but not all had postmarks. The only town in Belgium to have received a revolutionary name was CHARLEROI (containing the reference to royalty). It was for a period re-named LIBRE-SUR-SAMBRE, and only in manuscript. It is extremely rare with only a few known. The manuscript abbreviated name looks uninspiring and hyieroglyphic but it’s a prize. Some while ago I came across a quite different use of the name used as a transit mark on a letter from NAMUR to THUIN near Mons.

It’s the first known until somebody finds another one ! The town of EUPEN also changed its name for a time to NEAU, but this was a re-use of the old name of the town rather than a true revolutionary name. It is prized by collectors nevertheless, and may have been an attempt at avoiding the use of the Germanic name of the town. It is often treated as a revolutionary name but isn’t truly so. It’s a re-use of the old name probably for linguistic reasons. It’s reasonably scarce but an important requirement for collectors of the period.

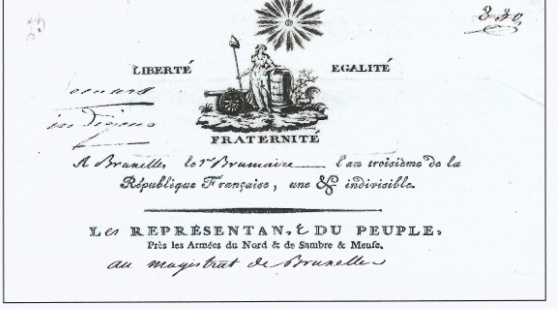

The Revolutionary Calendar

France adopted an entirely new “metric” calendar in 1791, with the year divided into ten equal months of thirty days named loosely after the seasons, with the odd days added on to each year as “jours complémentaires”. Before about 1800, mail usually included the use of this interesting dating system, and letters with the complementary dates are sought after.

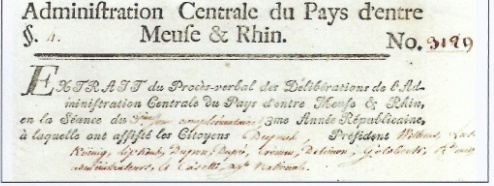

The System of “ Departments “

In 1792, as part of the total administrative reconstruction, France was divided into departments, most named after a geographical feature (except Jemappes), each in turn numbered from 1 to the mid 80s. As more countries were conquered, this system was in turn applied. Belgium was divided into nine departments numbered 86, and 91 to 98, with Brussels and surrounding Brabant being the departments of La Dyle with the number 94.

Postmarks showed the town name with the department number above rather like mileage marks and they were used to calculate postage which at one time was from centre to centre of each department regardless of distance. Postmarks were divided into three types ; for unpaid mail three examples from MONS in different colours are shown. (Blue very unusual). Most towns used only one colour of ink throughout the period. These are the most common style of mark.

Pre-paid letters are less common and usually have the letters PP either side of the number standing for port payé. Three nice examples here including a letter with an unpaid mark together with a paid mark, here on a letter from Antwerp.

A third rare type of mail is déboursé mail which had not been possible to deliver, and for which the charge had to be cancelled. These are in various styles. Double déboursé letters are very scarce.

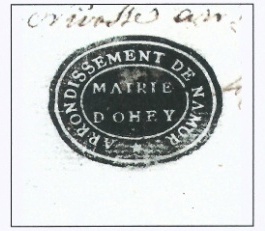

In turn, each department was divided into arrondissements (usually nine or so per department) and these in turn into cantons, all for administrative purposes. The full department name often appears in the address and just occasionally we find the arrondissement and canton name as well.

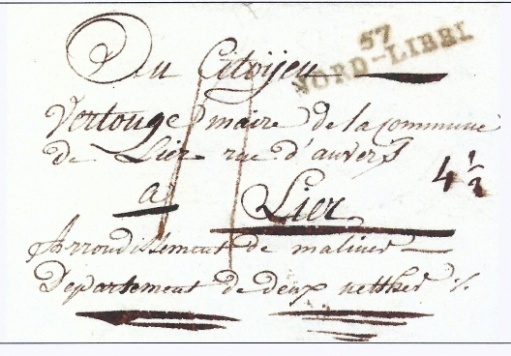

A perfect example :

letter dated 12 floréal an onze (2 may 1803) from NORD-LIBRE, the nom révolutionnaire for Condé-sur-Escaut in the NORD département to the Maire of the commune of LIER, arrondissement de MALINES, département des DEUX NETHES.

A perfect example :

letter dated 12 floréal an onze (2 may 1803) from NORD-LIBRE, the nom révolutionnaire for Condé-sur-Escaut in the NORD département to the Maire of the commune of LIER, arrondissement de MALINES, département des DEUX NETHES.

The letter is written in Dutch from a “Belgian” serving as conscript in the French Army. He addresses the Maire as “Burger”.

The System of Prefect and Maires

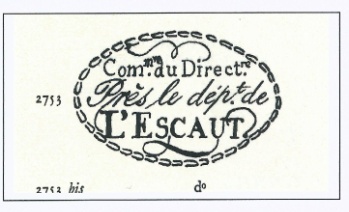

The Revolution brought with it a much more standardized system of administration which replaced that of the Ancien Régime’s. Each town had a maire, not always a local appointee and about 1800 each department had a préfet responsible to central government and he often had a cachet entitling him to free postage. Interestingly only one of the préfets in the “Belgian” departments was of Belgian origin (de coninck – préfet of Jemappes 1805-1810) largely because it was the custom to appoint préfets from outside their aera of origin. Nevertheless a number of Belgians were appointed as préfets in France and in other départements conquis.

The prefectoral system which is still used in France wasn’t introduced until the early 1800s and of course still exists. They are now called governors of provinces.

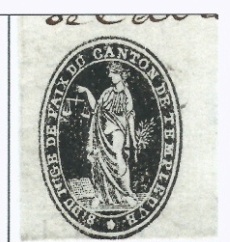

Each department was divided into arrondissements and then into cantons. Towns and arrondissements had a maire, as evidenced here. The prefectoral system was a truly Napoleonic invention, resulting from the creation of an elite corps of administrators to run the Empire.

Inevitably as well as the reorganisation into departments there were layers of administration. Here we have a list of officials for the town of NINOVE.

Franchise Marks

Administrators at all levels frequently had very attractive cachets to identify themselves and more importantly to authorize them to free mail. Those of the préfets are well known, but often those of local administrators or the cantons are very attractive but more difficult to find.

They too had cachets although one is manuscript (seen only once) but must be relatively common. I’ve added a couple of other good examples of cachets which can be of poor quality. The one from BRUGES is quite extraordinary !

They too had cachets although one is manuscript (seen only once) but must be relatively common. I’ve added a couple of other good examples of cachets which can be of poor quality. The one from BRUGES is quite extraordinary !

To finish, I have a run of letters of “postal” significance. An official circular to Masters of the Horse Posts ; some letters with interesting endorsements (“deliver this evening” ; recommandee ; by coach ; by barge), and some postal forms : a receipt for a registered letter of 1799, a packet receipt of 1808, an example of one of the postal innovations : few date stamps used in the period.

To end with something lighter – a prison letter regarding prisoners to be used on road maintenance “I request that they are well supervised by the guard and that they be made to understand the use of a shovel”.